The vagus nerve represents the main component of the parasympathetic nervous system, which oversees a vast array of crucial bodily functions, including control of mood, immune response, digestion, and heart rate. It establishes one of the connections between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract and sends information about the state of the inner organs to the brain via afferent fibers. In this review article, we discuss various functions of the vagus nerve which make it an attractive target in treating psychiatric and gastrointestinal disorders. There is preliminary evidence that vagus nerve stimulation is a promising add-on treatment for treatment-refractory depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Treatments that target the vagus nerve increase the vagal tone and inhibit cytokine production. Both are important mechanism of resiliency. The stimulation of vagal afferent fibers in the gut influences monoaminergic brain systems in the brain stem that play crucial roles in major psychiatric conditions, such as mood and anxiety disorders. In line, there is preliminary evidence for gut bacteria to have beneficial effect on mood and anxiety, partly by affecting the activity of the vagus nerve. Since, the vagal tone is correlated with capacity to regulate stress responses and can be influenced by breathing, its increase through meditation and yoga likely contribute to resilience and the mitigation of mood and anxiety symptoms.

introduction

The bidirectional communication between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract, the so-called “brain–gut axis,” is based on a complex system, including the vagus nerve, but also sympathetic (e.g., via the prevertebral ganglia), endocrine, immune, and humoral links as well as the influence of gut microbiota in order to regulate gastrointestinal homeostasis and to connect emotional and cognitive areas of the brain with gut functions (1). The ENS produces more than 30 neurotransmitters and has more neurons than the spine. Hormones and peptides that the ENS releases into the blood circulation cross the blood–brain barrier (e.g., ghrelin) and can act synergistically with the vagus nerve, for example to regulate food intake and appetite (2). The brain–gut axis is becoming increasingly important as a therapeutic target for gastrointestinal and psychiatric disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (3), depression (4), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (5). The gut is an important control center of the immune system and the vagus nerve has immunomodulatory properties (6). As a result, this nerve plays important roles in the relationship between the gut, the brain, and inflammation. There are new treatment options for modulating the brain–gut axis, for example, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and meditation techniques. These treatments have been shown to be beneficial in mood and anxiety disorders (7–9), but also in other conditions associated with increased inflammation (10). In particular, gut-directed hypnotherapy was shown to be effective in both, irritable bowel syndrome and IBD (11, 12). Finally, the vagus nerve also represents an important link between nutrition and psychiatric, neurological and inflammatory diseases.

basic anatomy of the vagus nerve

The vagus nerve carries an extensive range of signals from digestive system and organs to the brain and vice versa. It is the tenth cranial nerve, extending from its origin in the brainstem through the neck and the thorax down to the abdomen. Because of its long path through the human body, it has also been described as the “wanderer nerve” (13).

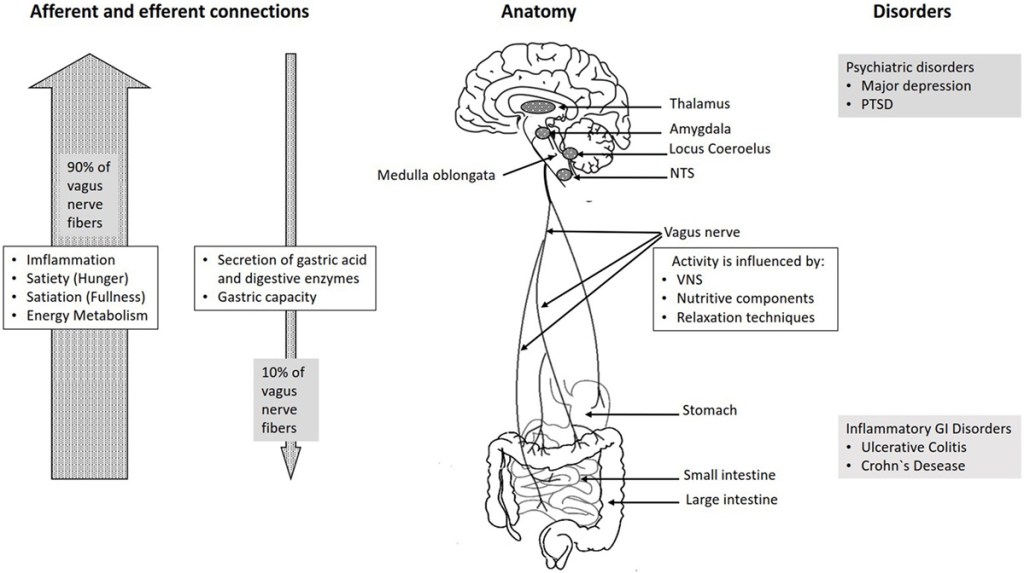

The vagus nerve exits from the medulla oblongata in the groove between the olive and the inferior cerebellar peduncle, leaving the skull through the middle compartment of the jugular foramen. In the neck, the vagus nerve provides required innervation to most of the muscles of the pharynx and larynx, which are responsible for swallowing and vocalization. In the thorax, it provides the main parasympathetic supply to the heart and stimulates a reduction in the heart rate. In the intestines, the vagus nerve regulates the contraction of smooth muscles and glandular secretion. Preganglionic neurons of vagal efferent fibers emerge from the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve located in the medulla, and innervate the muscular and mucosal layers of the gut both in the lamina propria and in the muscularis externa (14). The celiac branch supplies the intestine from proximal duodenum to the distal part of the descending colon (15, 16). The abdominal vagal afferents, include mucosal mechanoreceptors, chemoreceptors, and tension receptors in the esophagus, stomach, and proximal small intestine, and sensory endings in the liver and pancreas. The sensory afferent cell bodies are located in nodose ganglia and send information to the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) (see Figure 1). The NTS projects, the vagal sensory information to several regions of the CNS, such as the locus coeruleus (LC), the rostral ventrolateral medulla, the amygdala, and the thalamus (14).

Figure 1

FIGURE 1. Overview over the basic anatomy and functions of the vagus nerve.

The vagus nerve is responsible for the regulation of internal organ functions, such as digestion, heart rate, and respiratory rate, as well as vasomotor activity, and certain reflex actions, such as coughing, sneezing, swallowing, and vomiting (17). Its activation leads to the release of acetylcholine (ACh) at the synaptic junction with secreting cells, intrinsic nervous fibers, and smooth muscles (18). ACh binds to nicotinic and muscarinic receptors and stimulates muscle contractions in the parasympathetic nervous system.

Animal studies have demonstrated a remarkable regeneration capacity of the vagus nerve. For example, subdiaphragmatic vagotomy induced transient withdrawal and restoration of central vagal afferents as well as synaptic plasticity in the NTS (19). Further, the regeneration of vagal afferents in rats can be reached 18 weeks after subdiaphragmatic vagotomy (20), even though the efferent reinnervation of the gastrointestinal tract is not restored even after 45 weeks (21).

Role of vagus in the functions of the Autonomic Nervous System

Alongside the sympathetic nervous system and the enteric nervous system (ENS), the parasympathetic nervous system represents one of the three branches of the autonomic nervous system.

The definition of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems is primarily anatomical. The vagus nerve is the main contributor of the parasympathetic nervous system. Other three parasympathetic cranial nerves are the nervus oculomotorius, the nervus facialis, and the nervus glossopharyngeus.

The most important function of the vagus nerve is afferent, bringing information of the inner organs, such as gut, liver, heart, and lungs to the brain. This suggests that the inner organs are major sources of sensory information to the brain. The gut as the largest surface toward the outer world and might, therefore, be a particularly important sensory organ.

Historically, the vagus has been studied as an efferent nerve and as an antagonist of the sympathetic nervous system. Most organs receive parasympathetic efferents through the vagus nerve and sympathetic efferents through the splanchnic nerves. Together with the sympathetic nervous systems, the parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for the regulation of vegetative functions by acting in opposition to each other (22). The parasympathetic innervation causes a dilatation of blood vessels and bronchioles and a stimulation of salivary glands.

On the contrary, the sympathetic innervation leads to a constriction of blood vessels, a dilatation of bronchioles, an increase in heart rate, and a constriction of intestinal and urinary sphincters. In the gastrointestinal tract, the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system increases bowel motility and glandular secretion. In contrast to it, the sympathetic activity leads to a reduction of intestinal activity and a reduction of blood flow to the gut, allowing a higher blood flow to the heart and the muscles, when the individual faces existential stress.

The ENS arises from neural crest cells of the primarily vagal origin and consists of a nerve plexus embedded in the intestinal wall, extending across the whole gastrointestinal tract from the esophagus to the anus. It is estimated that the human ENS contains about 100–500 million neurons. This is the largest accumulation of nerve cells in the human body (23–25). Since the ENS is similar to the brain regarding structure, function, and chemical coding, it has been described as “the second brain” or “the brain within the gut” (26). It consists of two ganglionated plexuses—the submucosal plexus, which regulates gastrointestinal blood flow and controls the epithelial cell functions and secretion and the myenteric plexus, which mainly regulates the relaxation and contraction of the intestinal wall (23).

The ENS serves as intestinal barrier and regulates the major enteric processes, such as immune response, detecting nutrients, motility, microvascular circulation, and epithelial secretion of fluids, ions, and bioactive peptides (27). There clearly is “communication” between the vagal nerve and the ENS, and the main transmitter is cholinergic activation through nicotinic receptors (24). Interaction of ENS and the vagal nerve as a part of the CNS leads to a bidirectional flow of information. On the other hand, the ENS in the small and large bowel also is able to function quite independent of vagal control as it contains full reflex circuits, including sensory neurons and motor neurons. They regulate muscle activity and motility, fluid fluxes, mucosal blood flow, and also mucosal barrier function. ENS neurons are also in close contact to cells of the adaptive and innate immune system and regulate their functions and activities. Aging and cell loss in the ENS are associated with complaints, such as constipation, incontinence, and evacuation disorders. The loss of the ENS in the small and large intestine may be life threatening (Hirschsprung’s disease; intestinal pseudo-obstruction), whereas as loss of the vagal nerve in these areas is not.

Vagus nerve as a link between the Central and ENS

The connection between the CNS and the ENS, also referred to as the brain–gut axis enables the bidirectional connection between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract. It is responsible for monitoring the physiological homeostasis and connecting the emotional and cognitive areas of the brain with peripheral intestinal functions, such as immune activation, intestinal permeability, enteric reflex, and enteroendocrine signaling (1). This brain–gut axis, includes the brain, the spinal cord, the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic, parasympathetic, and ENS), and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (1). The vagal efferents send the signals “down” from brain to gut through efferent fibers, which account for 10–20% of all fibers and the vagal afferents “up” from the intestinal wall to the brain accounting for 80–90% of all fibers (28) (see Figure 1).

The vagal afferent pathways are involved in the activation/regulation of the HPA axis (29), which coordinates the adaptive responses of the organism to stressors of any kind (30). Environmental stress, as well as elevated systemic proinflammatory cytokines, activates the HPA axis through secretion of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) from the hypothalamus (31). The CRF release stimulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion from pituitary gland. This stimulation, in turn, leads to cortisol release from the adrenal glands. Cortisol is a major stress hormone that affects many human organs, including the brain, bones, muscles, and body fat.

Both neural (vagus) and hormonal (HPA axis) lines of communication combine to allow brain to influence the activities of intestinal functional effector cells, such as immune cells, epithelial cells, enteric neurons, smooth muscle cells, interstitial cells of Cajal, and enterochromaffin cells (32). These cells, on the other hand, are under the influence of the gut microbiota. The gut microbiota has an important impact on the brain–gut axis interacting not only locally with intestinal cells and ENS, but also by directly influencing neuroendocrine and metabolic systems (33). Emerging data support the role of microbiota in influencing anxiety and depressive-like behaviors (34). Studies conducted on germ-free animals demonstrated that microbiota influence stress reactivity and anxiety-like behavior and regulate the set point for HPA activity. Thus, these animals generally show a decreased anxiety (35) and an increased stress response with augmented levels of ACTH and cortisol (36).

In case of food intake, vagal afferents innervating the gastrointestinal tract provide a rapid and discrete account of digestible food as well as circulating and stored fuels, while vagal efferents together with the hormonal mechanisms codetermine the rate of nutrient absorption, storage, and mobilization (37). Histological and electrophysiological evidence indicates that visceral afferent endings of the vagus nerve in the intestine express a diverse array of chemical and mechanosensitive receptors.

These receptors are targets of gut hormones and regulatory peptides that are released from enteroendocrine cells of the gastrointestinal system in response to nutrients, by distension of the stomach and by neuronal signals (38). They influence the control of food intake and regulation of satiety, gastric emptying and energy balance (39) by transmitting signals arising from the upper gut to the nucleus of the solitary tract in the brain (40). Most of these hormones, such as peptide cholecystokinin (CCK), ghrelin, and leptin are sensitive to the nutrient content in the gut and are involved in regulating short-term feelings of hunger and satiety (41).

Cholecystokinin regulates gastrointestinal functions, including inhibition of gastric emptying and food intake through activation of CCK-1 receptors on vagal afferent fibers innervating the gut (42). In addition, CCK is important for secretion of pancreatic fluid and producing gastric acid, contracting the gallbladder, decreasing gastric emptying, and facilitating digestion (43). Saturated fat, long-chain fatty acids, amino acids, and small peptides that result from protein digestion stimulate the release of CCK from the small intestine (44). There are various biologically active forms of CCK, classified according to the number of amino acids they contain, i.e., CCK-5, CCK-8, CCK-22, and CCK-33 (45). In neurons, CCK-8 is always the predominating form, whereas the endocrine gut cells contain a mixture of small and larger CCK peptides of which CCK-33 or CCK-22 often predominate (42). In rats, both long- and short-chain fatty acids from food activate jejunal vagal afferent nerve fibers, but do so by distinct mechanisms (46).

Short-chain fatty acids, such as butyric acid have a direct effect on vagal afferent terminals while the long-chain fatty acids activate vagal afferents via a CCK-dependent mechanism. Exogenous administration of CCK appears to inhibit endogenous CCK secretion (47). CCK is also present in enteric vagal afferent neurons, in cerebral cortex, in the thalamus, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, and dorsal hindbrain, and functions as a neurotransmitter (45). It directly activates vagal afferent terminals in the NTS by increasing calcium release (48). Further, there is evidence that CCK can activate neurons in the hindbrain and intestinal myenteric plexus (a plexus which provides motor innervation to both layers of the muscular layer of the gut), in rats and that vagotomy or capsaicin treatment results in an attenuation of CCK-induced Fos expression (a type of a proto-oncogene) in the brain (43). There is also substantial evidence that elevated levels of CCK induce feelings of anxiety (49). Therefore, CCK is used as a challenge agent to model anxiety disorders in humans and animals (50).

Ghrelin is another hormone released into circulation from the stomach and plays a key role in stimulating food intake by inhibiting vagal afferent firing (51). Circulating ghrelin levels are increased by fasting and fall after a meal (52). Central or peripheral administration of acylated ghrelin to rats acutely stimulates food intake and growth hormone release, and chronic administration causes weight gain (53). The action of ghrelin’s on feeding is abolished or attenuated in rats that have undergone vagotomy or treatment with capsaicin, a specific afferent neurotoxin (54, 55). In humans, intravenous infusion or subcutaneous injection increases both feelings of hunger and food intake, since ghrelin suppresses insulin release (56). Therefore, it is not surprising that secretion is disturbed in obesity and insulin resistance (57).

Leptin receptors have also been identified in the vagus nerve. Studies in rodents clearly indicate that leptin and CCK interact synergistically to induce short-term inhibition of food intake and long-term reduction of body weight (40). The epithelial cells that respond to both ghrelin and leptin are located near the vagal mucosal endings and modulate the activity of vagal afferents, acting in concert to regulate food intake (58, 59). After fasting and diet-induced obesity in mice, leptin loses its potentiating effect on vagal mucosal afferents (59).

The gastrointestinal tract is the key interface between food and the human body and can sense basic tastes in much the same way as the tongue, through the use of similar G-protein-coupled taste receptors (60). Different taste qualities induce the release of different gastric peptides. Bitter taste receptors can be considered as potential targets to reduce hunger by stimulating the release of CCK (61). Further, activation of bitter taste receptors stimulates ghrelin secretion (62) and, therefore, affects the vagus nerve.

This article is part of the Research Topic

Nutritional Psychiatry: How do Brain – Gut Interactions Work?

Sigrid Breit1†

Sigrid Breit1†  Aleksandra Kupferberg1†

Aleksandra Kupferberg1†  Gerhard Rogler2 Gregor Hasler1*

Gerhard Rogler2 Gregor Hasler1*

- 1Division of Molecular Psychiatry, Translational Research Center, University Hospital of Psychiatry, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- 2Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Front. Psychiatry, 13 March 2018

Sec. Psychological Therapy and Psychosomatics

Volume 9 – 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044

Image Credit: